Looking Back to Move Forward: The Role of Retrospectives in Game Development

Including my guidelines and template for running retros that work

No matter how polished the roadmap or how well-planned the sprint the reality of making games is changing priorities, unforeseen obstacles, and lessons you only learn by doing. To make sure we learn and don’t just throw ourselves straight into the cycle again… we have retrospectives.

A retrospective is a deliberate and structured opportunity for a team to reflect on what happened during a recent sprint, milestone, or release. What went well, what didn’t, and what could be improved. It's so important to remember it's not about assigning blame or rehashing frustration. It’s to improve how the team works together moving forward.

In an industry that is all about iteration retrospectives are essential.

How Retrospectives Fit into Agile Game Development

In agile methodologies, especially Scrum, retrospectives are part of the core cycle. At the end of each sprint, the team gathers often alongside the Scrum Master or producer to reflect. In games teams this usually happens at the end of a two-week sprint, a feature milestone, or a major release like a beta or content drop.

Retrospectives are different from reviews or demos. They’re not about the work produced. They’re about the process that got you there.

That means they’re not just for designers or engineers. Artists, QA, producers, everyone involved in the delivery process should have their say. The best retrospectives are about cross-discipline insights.

Agile practices emphasise continuous improvement and retrospectives are the primary tool for making that happen in real time.

Running an Effective Retrospective

There are lots of formats for retrospectives but the most common and effective structure is simple: what went well, what didn’t go well, and what we should try next time.

This can be done as a group discussion, a sticky-note session, or a virtual board. Whatever suits your team size and culture. What matters most is that the environment feels safe and inclusive. And that the outcomes are actionable.

A good retrospective encourages honesty without finger-pointing. It looks for patterns rather than one-off frustrations. And it ends with a few small, clear action items. Not a wall of issues no one will follow up on.

We have to work out what needs attention and take a step towards improving it.

The most successful teams I’ve worked with make retrospectives part of their rhythm. They reflect often, adjust quickly, and treat process as something they can shape.

Common Challenges in Retrospectives

While retrospectives are simple in theory, running effective ones consistently can be tricky. Here are some of the most common challenges that come up.

People have to feel safe. If people don't feel like they can speak honestly there's no point. The retrospective just becomes a box-ticking exercise hand-waved away. Silent and polite. It happens when there's hierarchy in the room, or a new team dynamic people are still feeling out and not quite comfortable with, or a history of feedback being ignored so people feel there's no point. Curiosity is the key and that tone has to be set right from the start.

Then there's the opposite of polite silence: the blame and defensiveness. When everyone just wants to talk about who did something wrong rather than why it happened and how to do it better next time. It has to focus on the system and the processes. Productive retros look for the causes. It's not about handing out blame.

Another common problem is not following up. If nothing ever gets changed as a result of the retro everyone loses trust in the process. Issues that are raised need to be clear and tracked and actually actioned.

It can be fun to mix things up every so often. So that it doesn't start to feel stale and to keep everyone interested. Different formats, different facilitation styles, different tools.

There's a temptation to only run a retro when something has gone wrong. This is a mistake! High-performing teams reflect when things go wrong too. Then you can find out what's working and do more of it.

My Guidelines for Better Retrospectives

Over time I’ve developed a set of principles that help create a safe, open space where retrospectives are actually useful. They are less about process and more about mindset. How we talk to each other when we’re reflecting on the work, the team, and ourselves.

Here are the guidelines I bring to every retro I run. It was workshopped at a previous company and I've continued to use it:

No one has the truth or the right answer. Everyone sees things through their own lens. No one view is complete.

Nobody sees the whole picture. Insight comes from many perspectives. Assume others know something you don’t.

Everything is questionable or challengeable. Nothing is sacred. Not the process, tools, or decisions we made.

Everyone should contribute to see the full picture. The quietest voices often have the clearest observations. Make space for them.

No radicalisation. Avoid all-or-nothing thinking. There are no heroes and villains. Only systems and choices.

Use tentative language. Say “It seems like…” or “I noticed…” instead of absolute statements. Leave room for dialogue.

Reflect rather than judge. We're not here to criticise people! We’re here to understand what happened and why.

Listen and ask questions. Curiosity builds trust. Ask before you assert.

No generalisations. “Always” and “never” shut conversations down. Be specific and grounded in context.

Nothing is wrong. As long as you’re honest and respectful your perspective is valid. Even if it’s just yours.

When teams agree to these kinds of rules upfront and revisit them regularly they create a shared language for reflection. It lowers the stakes and raises the quality of what gets shared.

Retrospectives aren’t just about issues. They’re about building the culture you want to work in.

How I Run Retros: A Practical Template

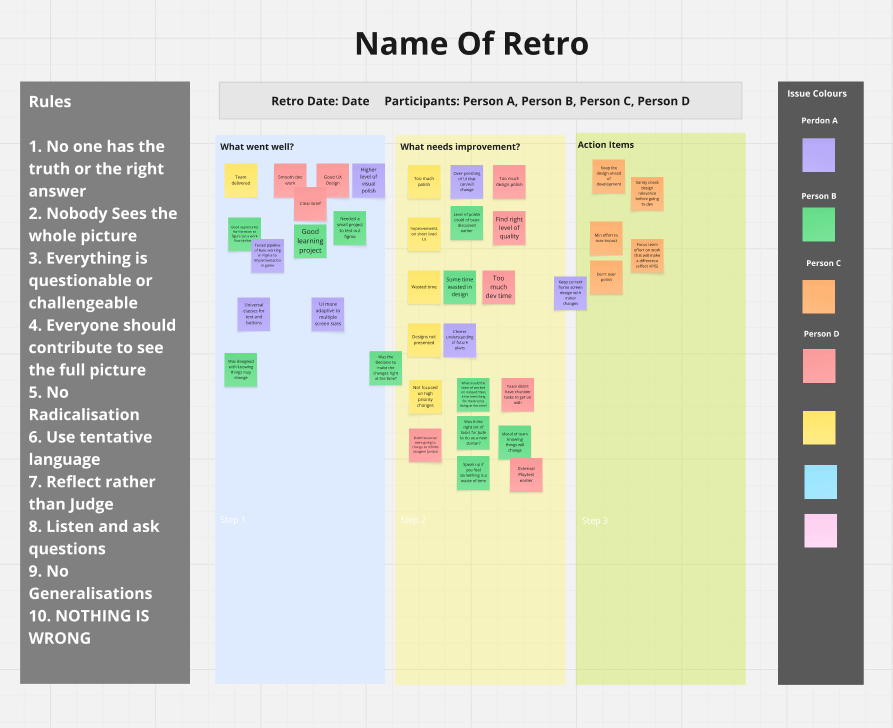

Here’s the basic template I use for the retrospectives I run. I typically set this up in Miro, but it’s easily replicable in any virtual whiteboard or collaborative tool.

Depending on what period I’m retroing with the team, I’ll run the session for anywhere from thirty minutes to an hour. Once you go beyond an hour energy and focus start to drop. The quality of discussion tends to go downhill after that point. So keep it tight.

If I’m running a sprint retro for a team of three to ten people I usually start by giving everyone about ten minutes of quiet time to think and record their thoughts on what went well and what could be improved. We use coloured sticky notes with each person using their own colour. This helps visually track who raised what and shows cross-team patterns quickly.

Once everyone’s notes are in we start with a random person and go through their items. As they read them out the other team members can chime in if they’ve written something similar. As we work through the board we put similar notes together and start to see themes emerging. This part of the session usually lasts ten to fifteen minutes depending on team size and the complexity of the sprint.

The final segment is focused on action. We identify three to five clear actions we want to take forward. No more. Each one gets assigned an owner - someone who’s responsible for making sure it’s followed up or implemented. It doesn’t mean they have to do the work themselves but they make sure it’s not forgotten.

And that’s it! Simple, structured, and scalable. It’s worked well across different teams and disciplines and it helps keep retros both productive and lightweight while still getting what we need from them.

What Bad Retros Look Like

I’ve experienced some shockingly bad retros over the years. So bad that I started to dread going to them.

Some of the worst ones took hours and still didn’t produce a single action item. We’d leave the room drained with nothing resolved - only to schedule a second (or third!) meeting to “finish unpacking it.” By then the momentum and any sense of being engaged or feeling comfortable and safe was long gone.

These kinds of retros usually pop up when something’s gone wrong and someone from up on high wants answers. Not to understand the system but to find the culprit. Or worse, to drag over every detail of the situation without any real intent to learn from it. Just put everyone in the stocks to throw rotten vegetables at them.

In those sessions there’s no interest in improvement. No focus on helping the team avoid the same pitfall next time. It stops being a retrospective and just becomes a police investigation. They don't help. Actually they make things worse because people stop sharing honestly and stop bringing up real issues. No one wants to put themselves in the firing line. There's no point in this kind of retro.

A retrospective should leave a team feeling clearer. Not told off or shamed. The goal is always forward motion. It's not a punishment.

Retrospectives are a Design Tool

Retrospectives aren’t just a box to tick at the end of a sprint. They’re a design tool. Not for features or content but for culture and communication and how we work together.

Done well, they make teams stronger. Not just because they find the problems but because they create space for shared ownership, honesty, and change. They remind us that process and culture is something we create together, not something handed down.